Standardized Swims and Routes

As previously defined, a swim route is a predetermined, abstract path between a start location and a finish location, composed of a straight line or series of connected straight-line segments.

Let’s further define a standard swim route as an established, recognized route used by most (or all) attempts of a given swim. A standard route is established either informally, through a history of successful swims along the route; or formally, by a sanctioning organization.

Finally, let’s define a standardized swim as a swim for which a standard route has been established.

Most well-known marathon swims are standardized swims, with standard routes:

- An English Channel swim, by default, covers the straight-line route between Dover and Cap Gris Nez.

- A Catalina Channel swim, by default, covers the straight-line route between Doctor’s Cove/Arrow Point and Point Vicente.

- A Boston Light Swim starts at Little Brewster Island and finishes at the L Street Bathhouse, via a meandering route among several islands in Boston Harbor.

Why does this matter? Consider the following hypothetical:

Perhaps I’m not satisfied with the typical English Channel route - I want to be different and special and do something no one’s ever done before. Perhaps I’ll start at Dungeness instead of Dover (adding ~6 miles to the total swim distance)!

How does the sanctioning organization (CS&PF or CSA) treat this swim, if it’s successful? Should it be recognized as a “first”? Or is it the same as any other English Channel swim (anywhere on the English shore to anywhere on the French shore)?

It is the sanctioning organization’s prerogative to recognize (or not recognize) more than one standard swim route. The English Channel and Catalina Channel organizations currently do not recognize multiple routes. Jim Fitzpatrick once finished a Catalina Channel swim at Newport Beach (~9 miles longer than the standard route), but it is recognized the same as all other Catalina-mainland swims.

Standard swim routes simplify matters for both the swimmer and the sanctioning organization.

- If there’s no recognition to be gained from a different route, most swimmers will simply choose the default.

- As more “standard route” swims are attempted, more knowledge is gained about the route, thus helping future swimmers.

- Swims along a single standard route are more comparable than swims along different routes.

- A sanctioning organization can simply list a successful completion of the standard route, without having to note the precise start and finish locations of each swim.

How Standard Swim Routes Develop: A Case Study

Consider the history of swims across the length of Lake Tahoe.

The first known lengthwise swim was completed by Fred Rogers in 1955, between Kings Beach in the northwest and Bijou in the southeast - a 20 statute mile route.

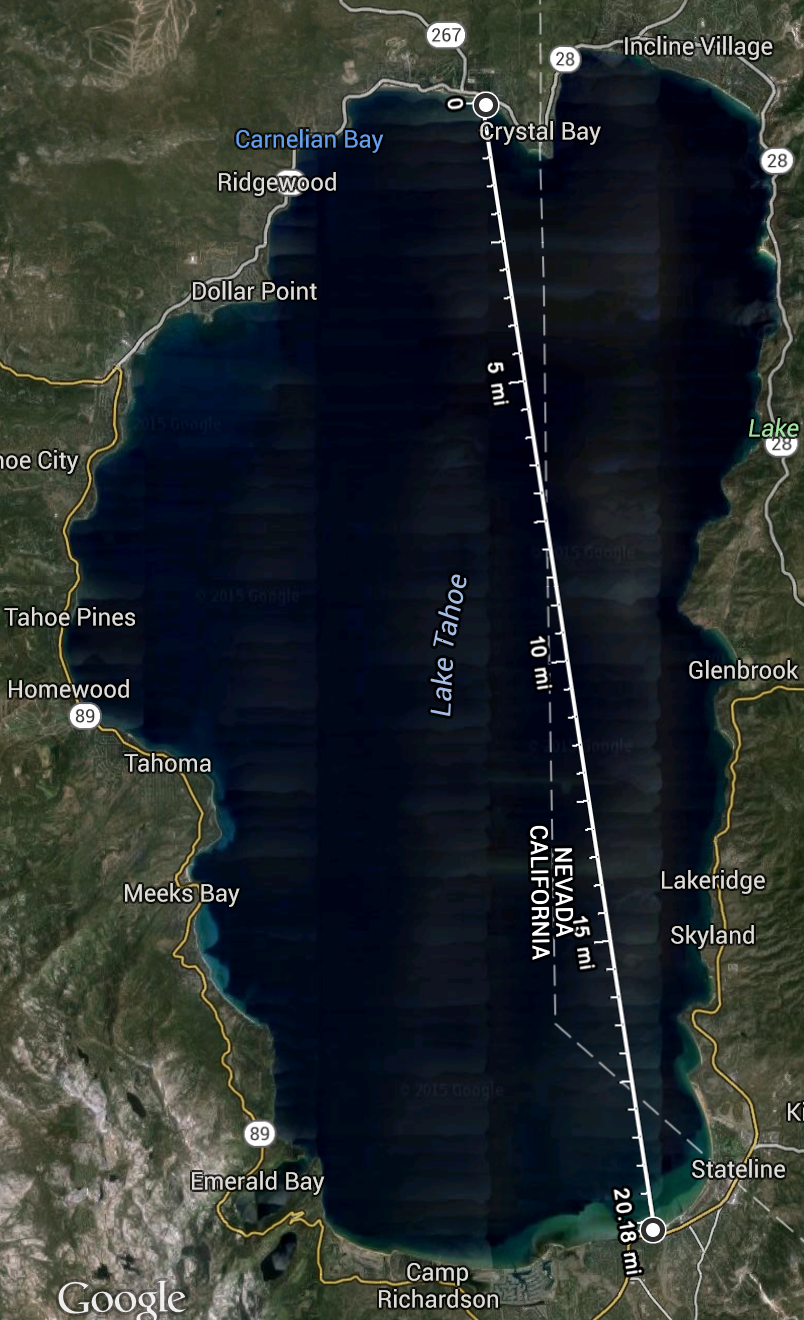

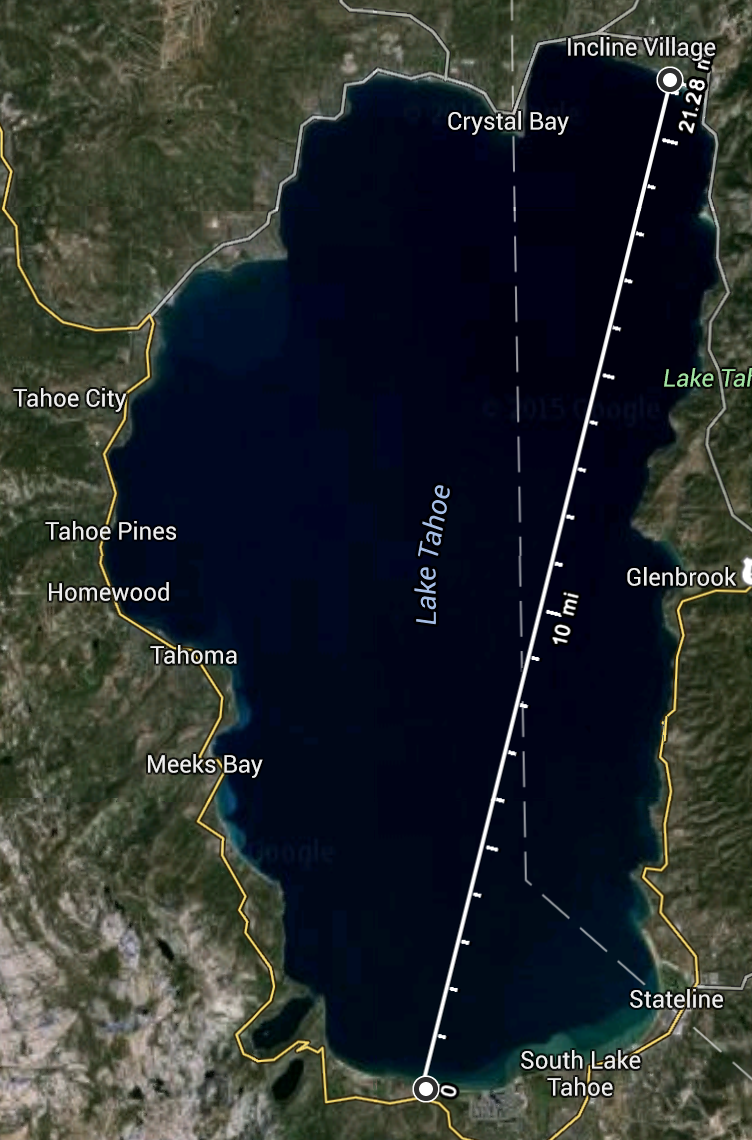

However, most modern (post-2004) Lake Tahoe lengthwise swims have used a different route, approximately 1.25 miles longer, between Hyatt Beach near Incline Village in the northeast, and Camp Richardson in the southwest:

The first to complete the Camp Richardson / Incline route was Laura Colette, in 2004. Subsequently, almost every lengthwise Lake Tahoe attempt has used this same 21.25-mile route. This is quite remarkable, given there is currently no functioning sanctioning organization for Lake Tahoe swims.

I asked Laura why she chose this route, and she confirmed my intuition: Because this route (southwest / northeast) covers the longest axis of the lake. Why does that matter? Because there can be only one longest route across a lake, but an infinite number of shorter routes. Therefore, it is a natural candidate for a standard swim route.

Before Laura Colette, eight swimmers had successfully swum the length of Lake Tahoe - using eight different routes ranging from 16.8 to 21.0 miles.

After Laura swam the longest-possible route (21.25 statute miles) in 2004, all subsequent Tahoe lengthwise aspirants were faced with the choice of either replicating her route, or doing a shorter route and opening themselves to the potential criticism of not doing a “full” lengthwise swim. Even in the absence of a sanctioning organization, Laura’s route became the de-facto standard.

Issues in Selecting Standard Routes

In planning new or unprecedented swims, one of the most important and subtle challenges is defining an appropriate swim route.

The route used by a “first” swim may have precedence in defining a standard route, but this can be over-ridden if consensus subsequently develops for a different route (as demonstrated in the Lake Tahoe case study).

Standard swim routes are usually simple and obvious.

- For a lake swim, there is only one longest route, but an infinite number shorter routes. If the longest route is a swimmable distance, it is usually a natural candidate for the standard.

- For a channel swim, there is only one shortest route, but an infinite number of longer routes. In this case, the shortest route is usually the natural candidate for the standard.

Standard swim routes define a minimum distance for a swim.

If the minimum distance is enforced by geography, the specific start and finish locations are less important.

Example: It’s impossible to swim a _shorter_English Channel swim than 20.5 miles. Even if an English Channel swimmer misses the Cap and finishes at Wissant or Aubresselles, we know they swam at least 20.5 miles. There is no concern about “cheating” the distance by finishing at a nonstandard location.

If the minimum distance is not enforced by geography, it is essential to start and finish at the specified locations.

Example: if you start and finish a Lake Tahoe swim at any location other than the southwest corner (Camp Richardson / Baldwin Beach area) and the northeast corner (Incline Village), you probably will have swum less than the standard distance of 21.25 miles. To complete a “full” lengthwise swim, you must respect the standard start and finish locations.

If there are multiple standard routes for a body of water, they should be categorically distinct swims - in terms of distance, conditions, and/or currents.

Examples:

- Lake Tahoe length vs. Lake Tahoe width (a ~10-mile route used for the annual Trans Tahoe Relay).

- Farallon Islands to Marin County mainland (Stewart Evans and Craig Lenning) vs. Farallon Islands to Golden Gate Bridge (Ted Erikson and Joe Locke).

- Santa Cruz Island to Ventura County (David Yudovin, myself, and others) vs. Santa Cruz Island to Santa Barbara County (Ashby Harper, Kevin Murphy, and others).

“Categorically distinct” is somewhat subjective, of course, but if multiple standard routes are truly justified, it should be obvious.

An unstandardized swim is a swim for which a standard route has not yet been established. In the next article, I will consider some principles and best practices in defining routes for as-yet-unstandardized swims.