Swim Report: Santa Barbara Channel, Santa Cruz Island to Oxnard

Part 1: Was it inevitable?

There it sits, tauntingly, every time I wade into the ocean. Dominating the southern horizon - as prominent a feature of the Santa Barbara landscape as chaparral-covered mountains, tile roofs, and beach volleyball. On clear winter days it’s a textured, multi-hued shadow. On hazy summer days it’s just a faint, misty outline. In the depth of June Gloom it disappears from view entirely - but I know it’s there.

The shadow is Santa Cruz Island – largest of the eight Channel Islands, 19 statute miles offshore from Oxnard, the closest part of mainland California.

Looking out at Santa Cruz Island from the mountains above Goleta. New Year's Day 2012. Photo by Vanessa.

The Impetus

A few months ago two local filmmakers asked: Would I be interested in being filmed for a documentary about marathon swimming in the Channel Islands? Would I help shed some light on this odd global subculture of people who swim across 3,000-foot deep ocean channels in the dead of night wearing nothing but a speedo, cap, and goggles?

It was an intriguing project. The wheels were set in motion, and it was soon decided (passive voice partially intentional) that I would try to become the ninth person to swim solo from Santa Cruz Island to the California mainland.

The History

Marathon swimming in the Santa Barbara Channel dates to the late 1970s. The two names to know are Cindy Cleveland and David Yudovin. In the midst of a golden age of Catalina Channel swimming, Yudovin and Cleveland both completed one-way Catalina solos in 1976 (11:50 and 11:04, respectively), and Cleveland followed up with a two-way in 1977 (24:30).

These intrepid marathoners then turned their eyes north, to the as-yet-unconquered islands of the Santa Barbara Channel. Yudovin and Cleveland both made dates with Anacapa Island for the summer of 1978. Yudovin made the first attempt and, in a story immortalized by Lynne Cox in Swimming to Antarctica, went into hypothermia-induced cardiac arrest a mile from the Oxnard shore. After technically dying, Yudovin was revived at a nearby hospital.

These intrepid marathoners then turned their eyes north, to the as-yet-unconquered islands of the Santa Barbara Channel. Yudovin and Cleveland both made dates with Anacapa Island for the summer of 1978. Yudovin made the first attempt and, in a Swimming to Antarctica_, went into hypothermia-induced cardiac arrest a mile from the Oxnard shore. After technically dying, Yudovin was revived at a nearby hospital.

So Cindy Cleveland, then, became the first to complete a Santa Barbara Channel swim on August 9, 1978 - a two-way Anacapa crossing in 12 hours, 48 minutes. This epic swim set up Cleveland’s Catalina circumnavigation (1979) and Monterey Bay crossing (1980) - two of the greatest feats in marathon swimming history.

Meanwhile, David Yudovin had unfinished business in the Santa Barbara Channel. After his brush with death, he returned to Anacapa and completed a one-way in 1982. And then, on August 16, 1983, he became the first to swim from Santa Cruz Island to the mainland (15 hours, 15 minutes).

Since then, seven others have added their names to the list. Ned Denison was the fastest, crossing in 10 hours, 27 minutes in 2006. One of Ned’s kayakers in 2006 (Ben) is one of the filmmakers behind DRIVEN. In a bizarre twist of fate, Ned also ended up in the hospital after his swim, with severe hypothermia. Crewing for him that day was… none other than David Yudovin. On the beach, as Ned was being carted off in an ambulance, an older paramedic recalled memories of another crazy idiot, 25 or so years ago, who almost died trying to swim across the channel. The paramedic didn’t realize he was talking to that very same man – David Yudovin.

The Gathering

They converged after-hours on a desolate dock. Fingers in the wind, gauging the unpleasantness in store. And for what? To spend the night on a boat, helping me accomplish some esoteric feat. It’s always humbling, these gatherings.

They’re a familiar cast of characters.

The frequently submerged gentleman, elite swim blogger, and adventure-beard-ist:

The ice swimmer, shark survivor, and Farallonista.

And the Olympian.

The crew were joined by observer Dave VM and Capt. Forrest of the Fuji III.

It took everything I had to make it across the Channel that night. And it would take everything they had to help me do it.

Part 2: Drop-Dead Conditions

Ventura Harbor. 9pm, September 14th.

ME: “How does the weather look?”

CAPT. FORREST: “Dogshit.”

He wondered whether perhaps I wanted to postpone the swim to another day. “What are your ‘drop dead’ conditions?” he asked. “It’s blowing 10 knots right here [i.e., in the harbor]. It’ll be worse out there.”

Here lay the dilemma: My crew and observer were here now. Dave and Rob drove down from SLO; Mark from SB (where he has two kids under the age of 3); Cathy from SF. We could, theoretically, delay for 24 hours - Cathy didn’t go home ’til Monday. But it would suck. I had already dragged these people out here in the middle of the night. Now I was going to send them all home (or to a hotel) and say we’ll try again tomorrow? Ugh.

Not to mention, the film guys were already on their way over to the island on a sail boat from Santa Barbara (a 4.5-hour trip). Would I call them and tell them to turn around?

There were no good options. The wind and waves were supposed to lay down after midnight. Maybe they would; maybe they wouldn’t. Tomorrow might be nicer; it might not.

Such are the logistics of marathon swimming that, at a certain point, you just have to take what the ocean wants to give you on a given day. I thought about the Hudson River during MIMS last year. I thought about the first half of my Catalina swim. And I made the call:

If it was swimmable, I was going to swim.

Outbound

The boat ride from Ventura to the island takes about two hours. Nobody slept. The Fuji is a great boat in many respects, but it’s not designed for sleeping. Everyone seemed in good spirits. The excitement of leaving the mainland at 15 knots is always more fun than the reality of trying to get back at 2 knots.

Within minutes of exiting the harbor, Rob was puking. Rob is a man of many skills, and one of them is the discreetness of his puking. It’s a casual, soundless puke. He leans over the gunwale and seems to be inhaling the fresh air of the open ocean, watching the bow wave careen into the distance. Cathy adds:

Only the spitting that follows the spewing belies the true nature of his tummy, the churning mass his guts have become as the boat rocks to and fro, again and again. Throughout the whole ordeal, his adventure beard remains unscathed, unsullied by gastric juices or the burger he ate for dinner.

As we motored out to sea, the lights of Ventura faded and the channel’s oil rigs - lit up like so many Christmas trees - grew looming and bright. Eventually, we left them behind too. It was, I noticed for the first time, really dark out here. I looked around for the moon but it wasn’t to be found. Apparently, I had scheduled my swim on a new moon!

We were all starting to wonder, “How much longer?” when Capt. Forrest cut the motor. We could just barely make out San Pedro Point, the easternmost edge of the island.

The Rock

The lack of moonlight would prove challenging throughout the night, but the first challenge was simply finding a place for me to start. While I changed into my swim attire and lubed up, Capt. Forrest, Dave, and the film guys were scoping out the craggy rocks and cliffs with flashlights (we had no spotlight). We ruled out trying to clear the water anywhere - too rocky, too rough. It was totally sketchy.

Eventually they found a rock face that seemed to offer a relatively smooth, semi-vertical surface (I wanted to avoid cutting myself up on barnacles or sharp edges). The Fuji was getting blown by the wind and had to circle around a couple of times to get me close. We launched Mark in the kayak. Ben was already on the water in a separate kayak, to film the start. Let’s do it. I jumped - and followed Mark and Ben to a rock I couldn’t see until I was almost on top of it.

I approached cautiously, head up, still wary of getting cut up and bleeding in these sharky waters. I let the waves carry me up and down the rock face - once, twice - getting a feel for the timing of it. Near the apex of the next wave I reached up, put my right palm flat on the rock - hopefully long enough to be observed from the boat. “Ready… go!”

I pushed off the rock and started swimming to Oxnard. The ocean floor dropped off quickly below me.

Part 3: Demons of Doubt

From the beginning, something just felt… off.

The chop disagreed with my stroke - pounding me randomly, from odd angles, making it impossible to develop any sort of rhythm.

The moonless night completely disoriented me. Shortly after the start we had a snafu with the glowsticks on Mark’s kayak, so it was insufficiently lit. He tried using a camping headlamp, but it was so blindingly bright that it seemed worse than the darkness.

It was a constant battle through the night - especially the first few feeds - to maintain a consistent distance from the boat and kayak. They were getting blown around by the wind; I was getting knocked around by the chop; and I had no depth perception to adjust to it.

I made 1.3 nautical miles of progress in the first hour - an incredibly slow pace for me. Possibly there was a head current near the island; but my constant zig-zagging didn’t help. I would bump into the kayak; Mark would yell at me; I’d try to adjust left but then get too close to the boat; Dave, Rob, and Cathy would yell at me; I’d try to adjust right; rinse & repeat. Occasionally, I’d actually find myself behind the boat (i.e., near the propeller), at which point Cathy screams and Capt. Forrest loses a month off his lifespan.

This may produce some entertaining documentary footage someday, but at the time it was fucking miserable - _for everyone. _

Around my 5th or 6th feed (a couple of which I didn’t keep down) the constant bumping and adjusting and yelling had decreased, but I began to notice something else: I wasn’t swimming well. The random chop and disorientation and mid-stroke adjustments had already taken a toll. I could feel the sloppiness and tightness creeping into my stroke.

The realization dawned on me: I might not finish this swim. I was doing the calculations in my head: At this pace, I could have another 10 (12?) hours in the water. After only 2 hours, I was exhausted and sick. (I had never gotten seasick while swimming!) I’m not sure I can do this for another 10 hours. I’m not sure I want to.

I could hear it in the voices of my crew: They knew all was not well. They had all seen me swim before. Something wasn’t right. Something was… off.

My thoughts drifted to them: my crew, my friends. Why am I putting them through this? They should be home, in bed - and so should I. This is a meaningless, selfish lark - and their suffering is pointless.

There’s a famous Ted Erikson saying: “Marathon swims are a dumb thing.” I knew exactly what Ted meant, right then.

I was ready to quit. I looked at the boat and thought, It would be better to be there than here. I thought about the film crew, the documentary, and how it would look on the big screen when I got on the boat. I didn’t care. I thought about the pre-swim publicity in Santa Barbara (which I didn’t ask for), and how I would explain to everyone back home how I quit after two hours. I didn’t care.

I kept repeating the phrase that always seems to be invoked after failed marathon swims: “It just wasn’t my day.” It had a comforting ring to it. It just isn’t my day.

The demons of doubt spoke quite powerfully to me that morning. But there was another voice - quieter but insistent:

There is nothing wrong with you, physically. You are making progress. Not great progress; not the progress you hoped; but progress. At this moment, nothing can prevent you from finishing except your own choice to quit.

For the next few feeds, I considered the two voices, the two options. And here’s the thing: I didn’t decide not to quit. But I put off the decision… for one more feed. And then another. And another…

Part 4: The Data

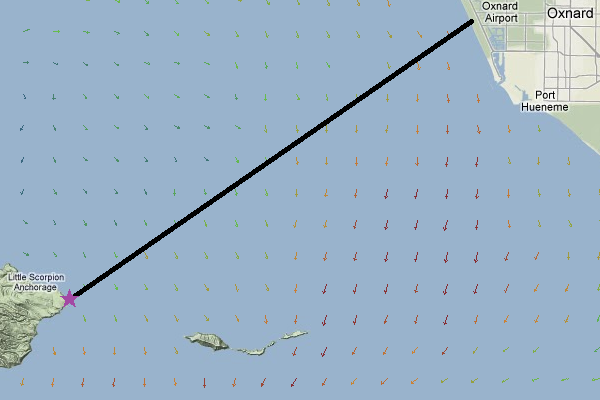

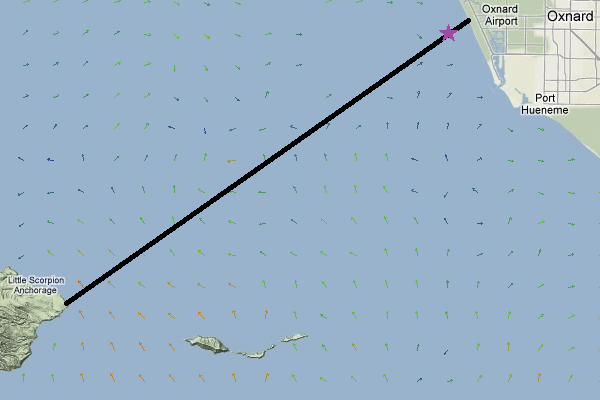

The shortest-line distance from Santa Cruz Island to the mainland is 16.4 nautical miles (18.9 statute) - starting at San Pedro Point, finishing at the southern end of Hollywood Beach, north of the entrance to Channel Islands Harbor. Capt. Forrest actually plugged in a slightly more distant waypoint - the resort at Mandalay Beach - which made it a 16.6-nautical mile swim. I don’t know why, but that’s what he did.

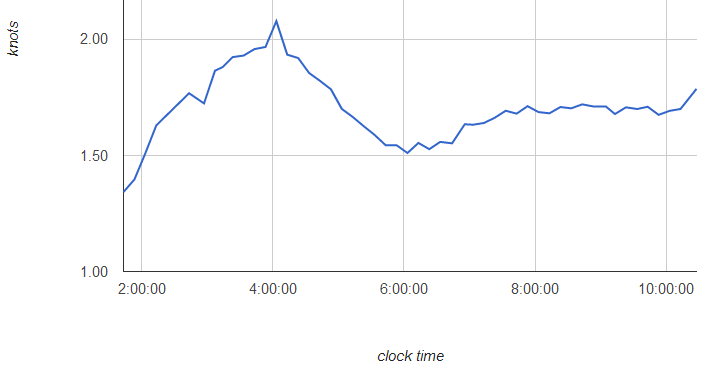

To break Ned’s record, I had to average 1.59 knots (2:02 per 100m, 2945m per hour) across the channel. To break 10 hours, I had to average 1.66 knots (1:57 per 100m, 3074m per hour). My neutral-condition (i.e., pool) pace for a swim of this distance, at my current fitness level, would be approximately 2.3 knots initially, fading gradually to ~2 knots.

My progress for the first five hours (corresponding to the nighttime portion of the swim) was as follows:

- Hour 1 - 1.4 nautical miles

- Hour 2 - 1.8 nmi

- Hour 3 - 2.0 nmi

- Hour 4 - 1.8 nmi

- Hour 5 - 1.5 nmi

Given my average progress over hours 1-5 (1.69 knots), the conditions may have been as much as a 20-25% “tax” on my swim speed. These conditions included a consistent Force 4 blow out of the West, only abating near the end. There were some surface currents, too, especially in the first couple hours. Here’s the SCCOOS model for that morning (click to enlarge):

1:00am (0:20 elapsed)

4:00am (3:20 elapsed)

7:00am (6:20 elapsed)

10:00am (9:20 elapsed)

After a slow “witching hour” (4-5 am, only 1.5 nautical miles), I made better progress after sunrise:

- Hour 6 - 1.6 nautical miles

- Hour 7 - 1.7 nmi

- Hour 8 - 1.7 nmi

- Hour 9 - 1.7 nmi

- Hour 10 - 1.8 nmi (pro-rated)

My stroke rate was my typical 64, with patches of 60. Nothing exciting there.

Part 5: The Test

Sometime between 2 and 3 in the morning, I had decided to spare everyone another (potentially) 10 hours of needless unpleasantness, and end my swim. I was just waiting for the right time. A convenient excuse. If Mark or Cathy or Rob or Dave had said at some point that night, “Evan, it’s pretty rough out here. Maybe you want to get on the boat and go home?”, I can’t say I’d have insisted on continuing.

It’s a testament to the loyalty and intestinal fortitude of my crew and observer that I never got that chance. Three hours later, I was still swimming.

At 5:30am, we were halfway across the channel - 8.3 nautical (9.6 statute) miles to go. At 5:45, the first hint of grey appeared on the horizon: nautical twilight. And it changed everything.

As any Catalina swimmer knows: The dark thoughts, the “witches,” are inseparable from the literal darkness of the night. Even the slightest hint of light changes everything. Instead of resolving to quit, I resolved to grind it out - however long it took. Instead of feeling that the Channel was punishing me, it now seemed that the Channel was testing me.

If you want this, you’re gonna have to work for it.

It was a test - and it had nothing to do with time or records. It was about confronting the darkness and vastness of the ocean, my own physical vulnerability and mental weakness - and finding a way to the other side.

When the sun rose on September 15th, I was more than halfway across the channel, and - despite all - still on pace to break Ned’s record (10 hours, 27 minutes). At that moment, I honestly couldn’t care less about the record.

Cathy replaced Mark in the kayak. It had been a stressful, physically demanding night for Mark, but he handled it like the Olympian he is. I think he felt responsible for keeping his old friend safe in a situation that often seemed anything but. He commented a few days later to Presidio Sports:

It was a humbling admission when I eventually told Evan that I needed to go rest on the boat, and it’s a true testament to his determination and conditioning that he didn’t quit along with me. Everyone from the boat captain to Evan and definitely everyone in between hoped that the conditions would get just a little worse, so we’d have a good excuse to stop. Unfortunately, the conditions were just barely good enough for us to keep trudging along.

After the sun rose, the filming kicked into gear again. I occasionally noticed Ben - decked out in full Frogman attire - cruise past me underwater with his GoPro. It was startling at first, but actually kind of fun. I can’t wait to see the footage. A preview frame:

Cathy paddled for the next three hours, until around 9am. A more patient, nurturing presence… and a comforting change of pace from Mark’s more verbal, taskmaster style (he is, after all, a swim coach - and a very good one).

At 9am I had about 2.5 nautical miles remaining - less than an hour and a half of swimming at my current pace. Cathy sensed I had hit another rough patch, and she was right. My shoulders throbbed painfully, and I was resorting to increasingly long stretches of backstroke. It was clear now I would finish the swim, but the record was in the balance.

Cathy and Rob made the call to wake up Mark and put him back in the kayak. His Olympian strength, his ability to motivate, was now needed.

Evan, we’re less than three miles out. You’re still under record pace, but there’s a good chance, if you pick it up, that you can break 10 hours. The choice is yours.

Those were Mark’s words shortly after he re-joined me. It was exactly what I needed to hear.

Almost simultaneously, the wind shifted… the chop settled down… and the swells were at my back. For the first time on this swim, the ocean let me find a rhythm. There was nothing left in my shoulders… but at the same time, there was nothing left to lose. I could see the beach.

9 hours, 47 minutes, 39 seconds after pushing off a vaguely menacing rock near San Pedro Point, my feet found dry sand on the shores of Oxnard.

I collapsed. Not because I lost consciousness, but because the weight of the past 10 hours was just a little too much to bear standing up.

The sun was high in a cloudless sky. A nice day at the beach.

What just happened. I’m still not quite sure.