Swim Report: Catalina Channel

The Jump

A few minutes after midnight, I stood on a platform off the Bottom Scratcher’s stern and eyed my destination: a small cove on the west side of Catalina Island, 100m or so distant, illuminated only by the boat’s spotlight and the soft glow of a crescent moon. The night was warm (69F), the wind calm, and the sky clear; the water (I was told) a benign 68 degrees. Against the engine’s soft murmur, I heard small waves lapping at the nearby shore. My crew surrounded me - quietly, supportively. It was time to begin.

I didn’t pause to contemplate the gravity of the moment. Let’s do this thing. The longer you stand there and think about it, the scarier it gets. So I jumped, or rather dove - head-first - into the inky sea.

I started stroking toward shore. Neil, already on the water in his foot-pedaled Hobie, followed alongside. I clambered over the thick kelp guarding Doctor’s Cove and found shallow water to stand up… then kept walking ’til I found dry rocks. I turned around and raised my arms above my head. Crickets chirped in the nearby brush. The stars shone startlingly bright. Offshore, Anne, Barb, Gracie, Neil, Amanda, Garrett, Mark, and Rob yelled some encouragement. I gazed across the vast, black expanse of water. Don’t think; just swim.

A Running Start

For the better part of the past year, I had been scared of this swim; but right now I wasn’t scared. Oddly, my thoughts turned to Pete Huisveld and Chad Hundeby. Pete and Chad swam two of the fastest Catalina crossings in history, but that’s not why I thought of them. Instead, I recalled a seemingly inconsequential detail from Penny Lee Dean’s History of the Catalina Channel Swims: When they began their swims, Pete and Chad literally ran into the water. For whatever reason, I found this hilarious.

So, I ran - and everyone got a good laugh. In retrospect, it was also a clever little mind-hack. I’m not scared of you, Catalina Channel. In fact, I’m so not scared of you that I’m going to run into the water to start a 20-mile swim. They say you should stand tall and confident when confronted with a mountain lion or grizzly bear. The same could be said of a channel swim.

After climbing once again over the famous kelp patch, I was soon on my way - head down, 65 strokes per minute, toward Point Vicente.

An Angry Ocean

The ride over on the Bottom Scratcher had been bumpy. So I wasn’t surprised when an angry ocean greeted us in the channel, beyond the protection of the island. Some Catalina swimmers luck out with calm seas; apparently I would not be one of them. I wasn’t happy about it, but there was nothing I could do.

I locked onto Neil, paddling a few feet to my right. Now was the time to find that zone - a zone of effortless speed, a focused mindlessness - and put as much distance between me and the island before the pain arrived (as it inevitably does). I swam “from feed to feed,” and the 20 minute intervals vanished into nothingness, like the phosphorescent bubbles trailing every arm-stroke.

At One with the Channel

There was a moment… I don’t know when, exactly - but it was O’Dark Thirty or thereabouts. I was settling into a comfortable rhythm and was coming to terms with the ever-increasing column of water beneath me. On my right, Neil paddled silently, stoically. On my left, most of my crew were either asleep or throwing up. I looked up for a quick “sight” to see if I could see any lights on the mainland. Nope - nothing but endless rolling swells. Above that, the stars seemed to shine brighter than ever before. In this moment, I had two thoughts.

First, I was struck - not for the first time, just more powerfully - by how utterly insane channel swimming is. Seriously - what the heck am I doing out here? It’s the middle of the night, and here I am, ploughing through whitecaps in the open ocean, wearing nothing but a speedo.

Second - and I think most channel swimmers will understand why this isn’t a contradictory thought - I was struck by how… beautiful it was. The image will last a lifetime: The moon, the stars, the swells, the chop… the black depths and fleeting phosphorescence.

I actually felt… comforted. As if the Channel were a living being, protecting me and willing me to shore. The Channel breathed through its swells, and laughed through its chop. The water itself - literally floating me above the inhospitable depths. It wouldn’t be easy, but right then - I knew I would make it across.

Here Comes the Sun

People say the toughest part of a Catalina swim is getting through the night. Once the sun rises, the glory of the day takes over - raising spirits and pushing you to the finish. I had the opposite experience. The night was the easy part! My shoulders were fresh, and there was nothing to see (around me or below me) to distract from the task at hand.

By nautical twilight (5:25am) I had been ploughing through chop for more than 5 hours. As the sky turned from black to grey, the ocean mercifully began to lay down. But the damage was done: My shoulders were spent! I asked for a hit of ibuprofen and went back to work. Around this time, Capt. Greg broke out his bagpipes - a traditional dawn ritual on the Bottom Scratcher. I didn’t hear it, but I think it was a welcome sound to my crew, who had endured a rough night on the sickeningly swaying boat.

The Coach

Shortly before 6am, Mark was launched on the second Hobie kayak, and paddled alongside Neil for a few minutes. Then, Neil dropped back and re-boarded the Bottom Scratcher, where a well-deserved nap awaited.

At a time when I was really descending into the hurt box, I can’t over-state how much it raised my spirits to see Mark. He’s my oldest friend, and a fellow marathon swimmer. I’ve swum more miles with him than any other single person. Actually, without him I probably wouldn’t have been there that day. It was Mark’s run for the 2008 Olympics that inspired me to give open-water swimming a try.

In his list of pointers for marathon swim crews, Rob described the importance of having someone on the boat “that knows you well enough to know when you’re doing good or when things are going badly. They should have enough of a grip on your personality to know how to motivate you when things get hard.” For me, Mark was that guy.

Mark was a constant source of encouragement. At 6:10am I took my 18th feed. Word from the wheelhouse was that I had 5.42 nautical miles remaining - almost exactly 10K. Mark translated this information as, “All you have left is a long workout. 10K is just a long workout - and you’ve done a lot of them.” It was exactly what I needed to hear at that moment. Later, when my technique started slipping, Mark reminded me to drive more with my hips to take some of the burden off my shoulders. Again - exactly what I needed to hear.

A couple hours later, Mark guided me all the way into shore - through the kelp and almost into the surf zone. At the last moment, before I bodysurfed into the rocks at Point Vicente, he said, “Evan, you’re about to join the crazy-man club.” He was the first to raise his arms in triumph when I stood up.

Company

At 6:30am I stopped for my 19th feed; the sun had risen 8 minutes previously. As I downed the Maxim, Gracie swam up alongside me. A swim buddy! Again, I can’t overstate how much it helped - at that moment - to have company. After my experience crewing for Cliff the week before, I had requested no pacers during the night. But now, with light in the sky and throbbing shoulders, it was perfect.

Gracie paced with me for the full hour allowed by CCSF rules. During my 21st feed break, before the last 20-minute segment with Gracie, I challenged her to a “race.” Obviously, after 7 hours of swimming I was no match for her - but it was fun to pretend. By “pretending” to race, I was able to (temporarily) access a previously hidden well of energy. For 20 minutes, at least, I was once again storming down the Hudson. For a little while, the adrenaline masked the pain. It’s mind-hacks like these that get you through a channel swim.

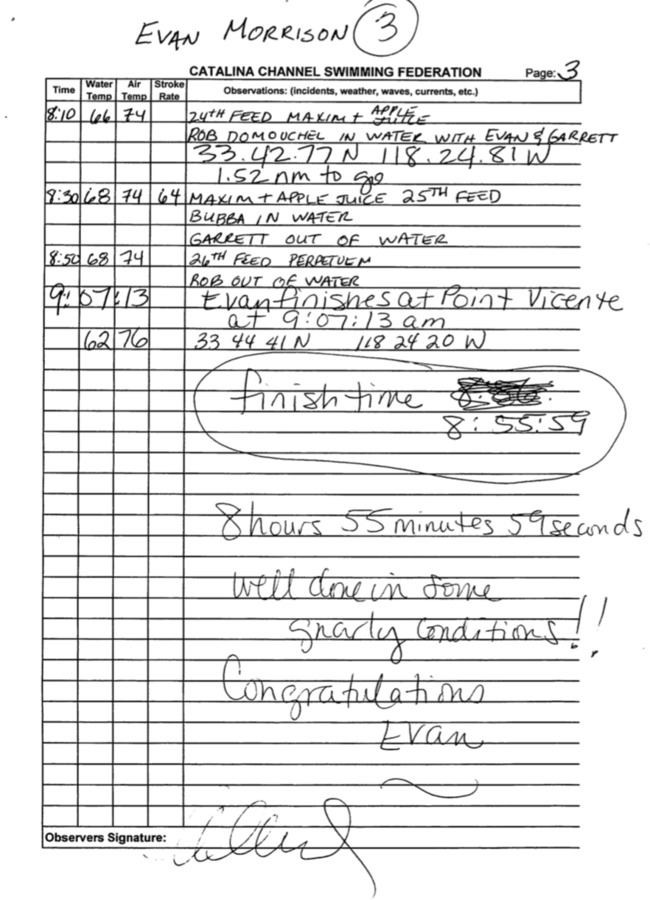

At 7:50am, after 20 minutes on my own, my brother Garrett jumped in to pace-swim - despite having puked his guts out all night. At 8:10, Rob D. joined us. At 8:30, Garrett got out. At 8:50, Rob got out. The water temp had abruptly dropped from 66-68F down to 62, as we hit the upwelling from the sharply inclining ocean bottom. Almost there.

The Finish

As the clock ticked past 9am, I encountered another giant kelp patch, even bigger and denser than the one at Doctor’s Cove. I was in less than 100 feet of water. I could see my parents on the beach. The rest of the story, in pictures…

Slippery rocks; uncoordinated swimmer:

Searching for dry land:

Forrest Nelson came to see me finish!

I will always be grateful: Neil and Gracie, the all-stars of swim support. Anne and Barb, for making sure the trains ran on time even though it wasn’t your job. Amanda, for your wacky humor and stellar camera-work. Rob, for being you. Garrett, for taking the plunge on an empty stomach. And Mark, for always being there when it matters.

The clock stopped a few ticks after 9:07am. 8 hours, 55 minutes, 59 seconds after leaving the island.

That’s how it happened, anyway - that “freshwater swimmer” earned his saltwater chops.

- Rob Aquatics report.

- Video, compiled from footage by Amanda:

GPS Analysis

I covered the first 5 miles in 2:06:50 (25:22 per mile), my fastest pace of the swim despite big swells and chop throughout the night. I was 12 minutes slower for the second 5-mile chunk (27:44 per mile), probably because I was plowing through the same waves and chop, but with substantially less fresh shoulders.

I hit the halfway mark (10 miles) at 4 hours, 25 minutes. So, contrary to our calculations at the time, I actually wasn’t on pace for a low-8 hour swim. In fact, I was on pace for pretty much what I ended up with - just under 9 hours.

In the second half of the swim I ran into the strong NW-to-SE cross current that had bedeviled many recent Catalina swims. Notice how my tracks “bow out” to the right of the “ideal” path, especially around 15-16 miles. The current is pushing me away from the finish (toward Long Beach), and the boat is forced to turn almost due north (against the current) to hit Point Vicente.

Despite the adverse current I held my pace steady - 2:13 (26:42 pace) for miles 11-15 and just under 2:17 (27:22 pace) for miles 16-20 - including some slow kelp crawling at the end. Indeed, my two 10-mile splits were within 5 minutes of each other: 4:30:28 vs. 4:25:31.

Coda I: In the History Books

From Penny Lee Dean’s authoritative History of the Catalina Channel:

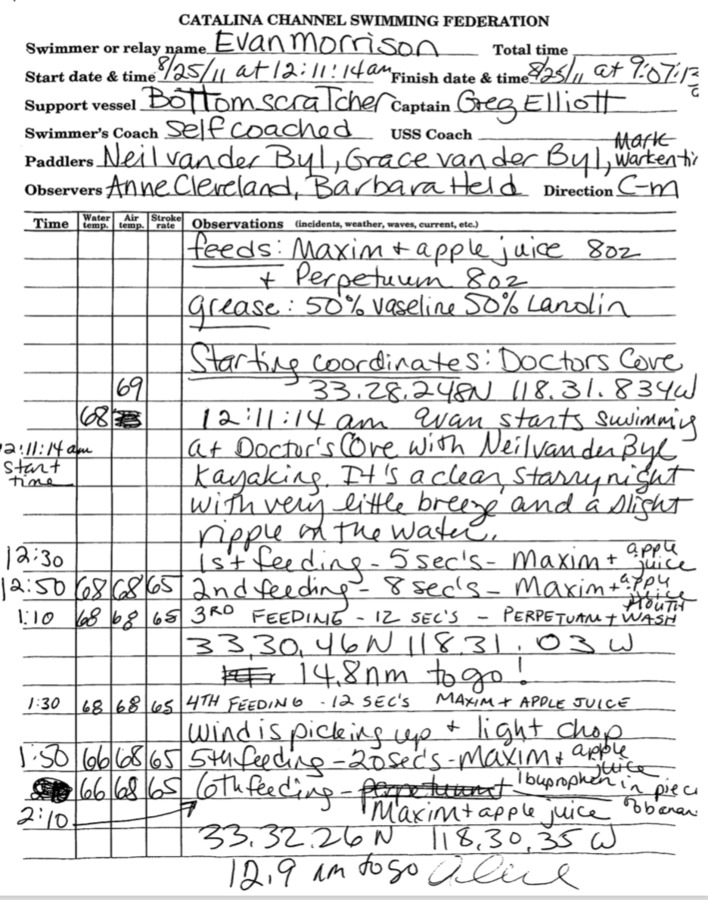

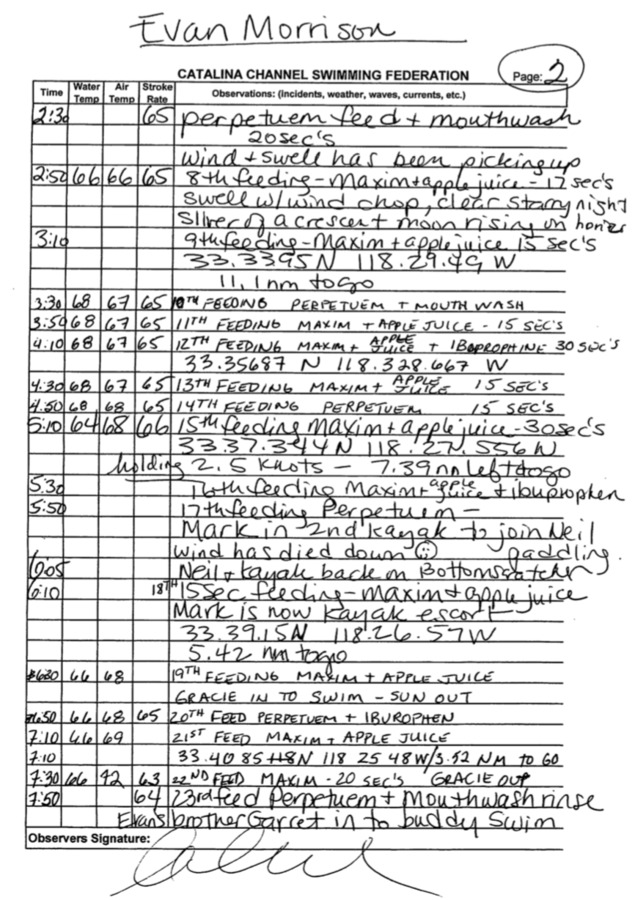

Next came Evan Morrison from Chicago to conquer the Catalina Channel. He swam on August 25th. Evan put a layer of grease on himself prior to the start. It consisted of 50% Vaseline and 50% lanolin. Evan swam from Doctor’s Cove on the Island, leaving at 12:11 am. It was a starry night with a light breeze and slight ripple, as reported by the log.

Within the first hour and a half the wind picked up, as did the swells. By 5:50 am the wind had died down and thus the swells. The ocean’s water temperature was 68 degrees at the swimmer’s launch into the water. At 5:10 in the morning it fell to 64 degrees but snuck back to 66 degrees or higher until just before the finish when it plummeted to 62 degrees.

Meanwhile the air temperature started at 68 degrees and rose to a warm 74 degrees at the finish. This helped to balance the cold water.

Evan had an excellent food plan. He took a break every twenty minutes. On his breaks he drank 8oz of Maxim with apple juice or 8 oz of Perpetuem. During the swim he also had a few Ibuprofens in a piece of banana, and mouthwash. His breaks were fast, from five seconds to thirty seconds.

Evan had an excellent stroke. He breathed to both sides and maintained 65 strokes per minute on his swim. Rarely did he change this.

Evan’s GPS landing at Cardiac Hill was 33.44.41 N 118.24.20 W. He arose on the mainland after 8 hours, 55 minutes, and 59 seconds. He was the 212th person to swim Catalina.

Coda II: Anne Cleveland’s observer log